“I was going to do whatever I wanted”:

Stephanie Wambugu on her career as a writer and editor

December 30, 2025

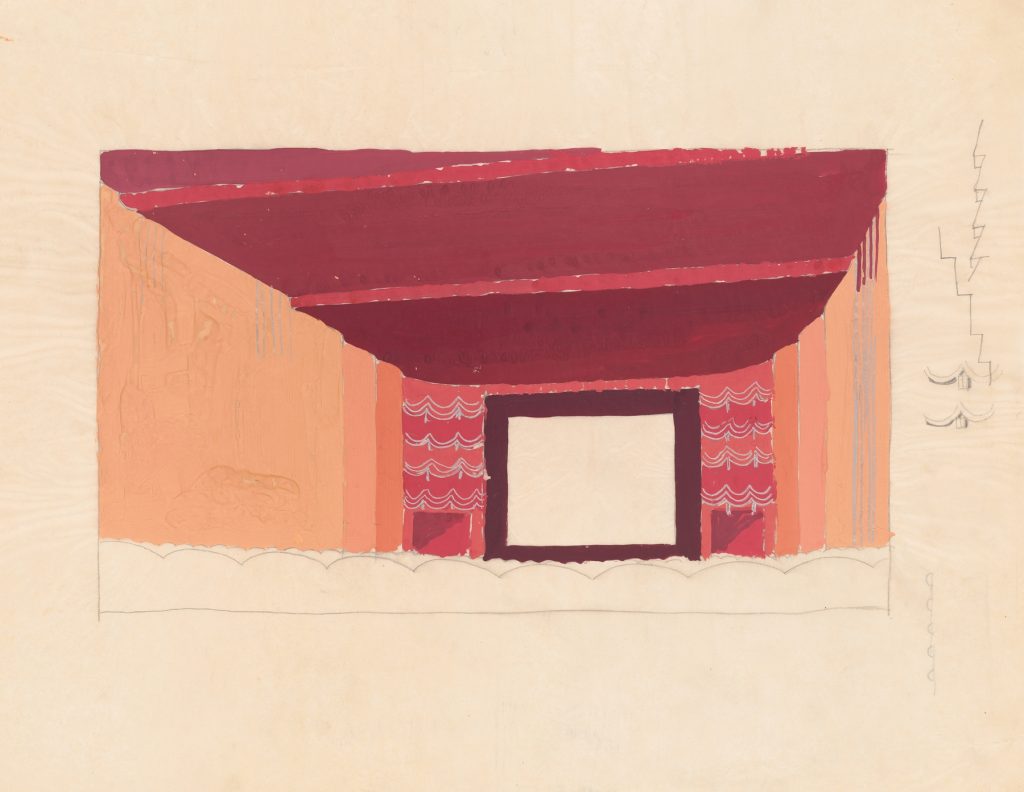

Winold Reiss, “Design proposals for Puck Theater, New York” (1941)

Editor’s note

With her celebrated debut novel, Lonely Crowds—which has been hailed as both the book of the summer and a best book of 2025—Stephanie delivers a moving, Ferrante-like study on the complexities of female friendship. It’s a mark of distinction that is evident from its first pages: “When I met Maria,” her narrator states, “I learned that without an obsession life was impossible to live.”

The book’s characters contend in compelling ways with questions of professional success and what it means to build a meaningful life through the decades. In our interview, Stephanie details her journey from aspiring poet to Columbia-trained fiction writer, sharing glimpses of the characteristically of-the-moment manuscripts currently taking shape on her desk.

Jana M. Perkins, PhD

Founder, Women of Letters

Stephanie Wambugu is the author of the novel Lonely Crowds. Her work has appeared and is forthcoming in Granta Magazine, The Drift, The Nation, Bookforum and elsewhere. She was born in Mombasa, Kenya and lives and works in New York.

How did your childhood shape your ideas about what work looked like and what was possible for you?

Stephanie Wambugu: My parents had to work very hard to forge a life in the United States. I won’t go into detail because a version of this story about immigration has been told ad nauseam. I’m cautious about any category as broad as “immigrant fiction” but I do think that this moment necessitates a renewed interest in fiction about citizenship, borders and state violence that is not cloying or sentimental or moralistic, but is simultaneously as absurd and as serious, and as strange, as the conditions we are living under today.

Anyway, throughout my childhood I saw my parents as industrious, resourceful and serious adults, people who seemed to have concerns that went beyond materialism and popular culture. I thank them for that. They always seemed ancient to me, compared to other parents, but they were relatively young (I was born on my mother’s thirtieth birthday; my parents are the same age) and that’s probably why I have the personality that I do and write about what I write about: generational schisms, secularization, the domestic.

I look around and don’t see many people like my parents anymore and it’s partly because I’ve opted to be a writer in a city where people sometimes come in order to postpone maturation and aging, to prolong adolescence and young adulthood indefinitely. I’m troubled by the desire of many adults around me who seem to want to infantilize themselves, who do not seem to want to be responsible for themselves, let alone other people. I think that the way I live (an artist in a major city) could not be more different from my parents (middle class professionals in suburban towns), but they never discouraged me from becoming a writer or generally living as I pleased.

It was inevitable, in any case. I was going to do whatever I wanted, but I take the responsibility of supporting myself and creating stability for myself very seriously and I credit my parents for that even though we have organized our lives in drastically different ways.

Fast-forward to today. How did the path to what you’re doing now unfold?

Stephanie Wambugu: I kept detailed diaries all throughout my childhood, but threw them in the garbage in an act of teen angst, I guess, when I was around nineteen.

I always wanted to be a poet. At the Catholic girls high school I attended, there was a sort of informal poetry club and it met on Friday afternoons, basically everyone there was a lesbian and eccentric, which was sweet. I wouldn’t say I was friends with any of the other members of the club (because of my aversion to clubs of any kind), but I loved writing and though it’s funny to think about being that self-serious as a teenager, I took it very seriously. In high school, I loved Robert Frost, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Lucille Clifton.

In college, at Bard, I loved June Jordan, Aimé Césaire, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery. I began as a poetry student, but after taking a workshop with the novelist Dinaw Mengestu, I began to write fiction. My undergraduate thesis was a novella set in Boston before the War on Terror; it followed two half-sisters (one a layabout, a former flight attendant, and the other a rich housewife married to a Black American doctor). Their father was a Kenyan polygamist priest and here they are living really secular lives in the United States as fairly modern women and the dissonance is difficult for them, just as the dissonance is difficult for Ruth in my novel Lonely Crowds.

I complained about Bard while there relentlessly because I was too young to allow myself to be happy (and because that’s what Bard students do) but I was so porous there and I learned a lot very quickly. I was exposed to a much broader canon of writers than I might have encountered at any other school because the faculty is so interesting and so varied. Right now, I am attending a residency in the Hudson Valley, only a few miles away from Bard, and it remains, to me, one of the most beautiful and evocative landscapes I’ve ever spent time in.

After Bard, I went to Columbia for an MFA in fiction. I came to New York with a decent severance from an art job I had and that paid for a few months of my expenses. I also taught undergraduates during my program through a fellowship that covered tuition and came with a modest salary. In graduate school, I also worked at the Noguchi Museum, at McNally Jackson Books and did a string of other jobs. I say all of this so as to say it was a very busy time for me, a tiring time, and I really don’t know where I found the energy.

I wasn’t very happy in graduate school and I found the seclusion required to write my first book fairly painful, but in retrospect, it was a transformative and transitional time for me. It’s maybe corny and New Age to talk about transformations and transitions, but I think I became an adult by working that much, spending that much time alone and writing my novel.

Tell us about some of the projects, ideas, or questions you’re currently working on.

Stephanie Wambugu: I am working on a novel that is set in 2024 during the time when campus activism was covered widely in national media. The novel is titled No Use and it’s about a young woman named Claudia who is in her senior year when she is arrested and then expelled from an Ivy League University for participating in a protest, a sit-in, that she felt ambivalent about but ultimately chose to attend.

She loses her housing, her access to dining halls. The older, more militant PhD candidate and union organizer she is dating is no help. Her former film professor is sympathetic and tries to help her in any way he can, though he ultimately can’t get her back into the University—the expulsion is final. He finally agrees, albeit reluctantly, to set her up with a job as a typist and assistant with his estranged father with whom he has not spoken for more than ten years. His father is a well-known and emotionally frigid novelist who has turned away from public life, much like the writer Henry Roth did. While Claudia finds both the father and son seductive, she is drawn to each man for starkly different reasons. It’s written in third-person, unlike my first novel. It has more to do with men and history than my first novel does.

I’m also revising a collection of stories called Name & Pronouns written in the first person. They’re mostly comic stories that satirize auto-fiction in that they are about people who are not me, but are written in a mock-confessional style. In these stories, people monologue about their erratic behaviour while being totally convinced that they are behaving normally. My thesis at Columbia was a story collection and many of these pieces emerged out of that, but their relationship to auto-fiction and how these stories might be reflective of my reticence about writing about myself was something I only understood very recently, while reading some of this fiction to another writer I know.

I recently wrote a piece in The Nation about Woody Allen’s vision of New York as a playground for rich bohemians, his endorsement of Andrew Cuomo and how a director or politician’s cinematographic vision of the city is reflective of their vision of the future and what is politically possible. I’m working on some other non-fiction and to quote my friend Tess Pollok, “the great thing about writing an essay is that it shows you the workings of your own mind in an often surprising way.”

What do you wish you’d started doing sooner?

Stephanie Wambugu: Sleeping nine hours each night. Women need more sleep. It’s truly impossible to write as much as I would like to write each day after having a late night.

I’m very social. I love to talk to people and go out, but too much of that and it can come at the expense of your work. I need to retreat in order to finish my second book. There’s no way around it, as far as I know. Writers need many hours alone and need to be lucid. I love John Cheever as much as the next person, but the fantasy of an inebriated, dazed genius is, for most people, just a fantasy.

Most people benefit from sleep, routine, three meals a day, an organized work space, and the like. For those who can’t sleep I recommend taking a bath with Dr. Singha’s Mustard Soak and spraying topical magnesium on the soles of your feet.

What book have you most often gifted to others?

Stephanie Wambugu: Horse Crazy by Gary Indiana.

When you think of women who have inspired or influenced you, who comes to mind?

Stephanie Wambugu: An endless list: the novelist Jean Rhys, the filmmaker Kathleen Collins, Assata Shakur, the actress Gena Rowlands, the director Elaine May, the photographer Diane Arbus, the singer Billie Holiday, the writer Tove Ditlevsen, the jazz musician Alice Coltrane, the sculptor Beverly Buchanan, the painter Cecily Brown, the artist Howardena Pindell, the director Sarah Maldoror whose excellent film Sambizanga I had the privilege of watching last month, followed by a wonderful Q&A with her daughter Annouchka de Andrade.

Outside of your work, what’s something you feel you’ve thought about more deeply than most other people?

Stephanie Wambugu: I’m not sure that I think about it more deeply than other people, but I think a lot about food waste and the impoverished quality of food in the United States. I love to cook and if I hadn’t become a writer, I would probably have tried to open a restaurant. I joke to myself about opening a Kenyan restaurant once I am done writing, but a few dinner parties will probably have to suffice. Cooking is also just the best way I know of reconnecting with the physical world, with reality, after spending time immersed in the fictive world of writing. It’s physical, practical, it brings you back to the dailiness of life and is a reprieve from the cerebral.

What’s a commonly shared piece of advice that you disagree with, and why?

Stephanie Wambugu: Write what you know. That’s bad advice. People need to be more inventive.

A writer like Iris Murdoch, for example, impresses me because of her ability to build a cast of people and fabricate a setting that you don’t doubt or disbelieve for a moment, even in the most outlandish moments. There is of course some excellent auto-fiction, but a lot of it suffers from myopia and solipsism, and it is worth considering that there is still something meaningful about constructing characters and that what you make up, even if it is realist, may be more interesting than the conversation you had at a bar in downtown Manhattan.

What keeps you going?

Stephanie Wambugu: Curiosity about what will happen. My life has changed drastically in the past year in numerous ways. I’m sure I’m experiencing or on the precipice of changes that I can’t anticipate as I write this now.

I also think the possibility of a more just world, a more equitable world, a less philistine world, a world where people are not so emotionally deadened, apathetic and unhappy is enough to write and live for. I hope the world is not just going to be made worse by demonic algorithms and callous governments and corporations, since I want to have children and I love being alive.

Where can our readers find you?

Stephanie Wambugu: stephanienjeriwambugu.com and @stephanienjeriwambugu on Instagram.