“I went back to what I’d always been passionate about”:

Petya K. Grady on her career as a writer, featured Substacker, and UX strategist

December 16, 2025

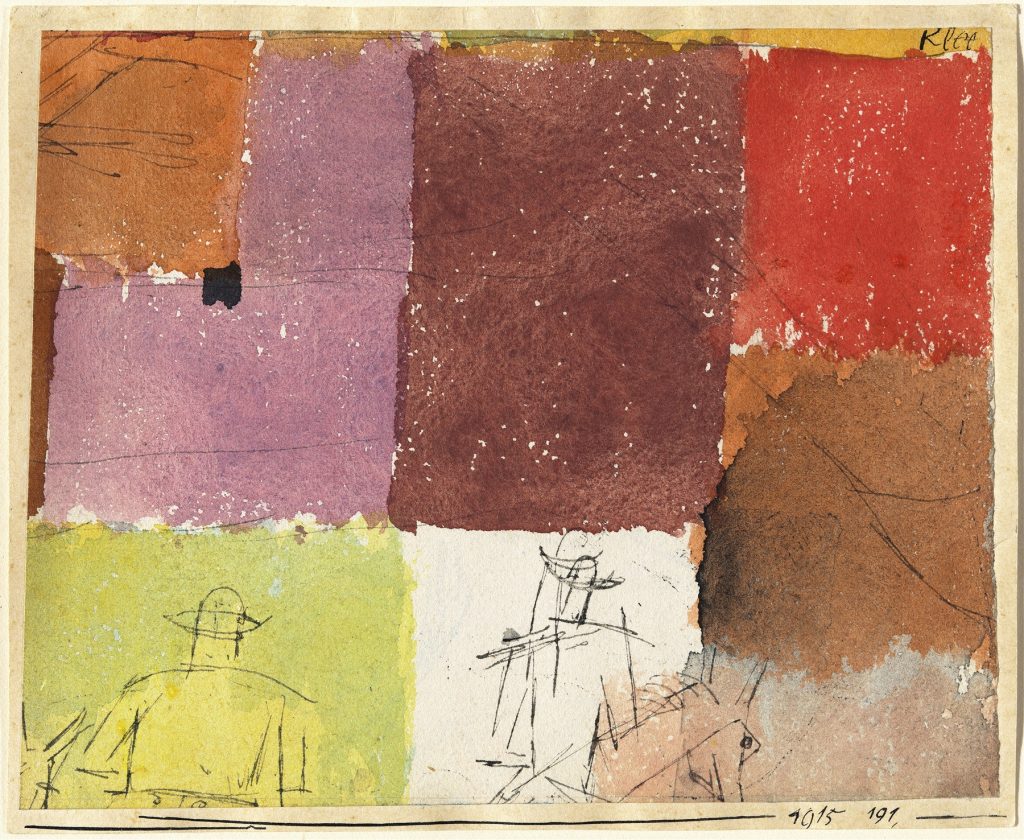

Paul Klee, “Composition with Figures” (1915)

You can listen to this interview on Substack, Apple Podcasts, or Spotify.

Editor’s note

With her work on A Reading Life, Petya’s newsletter exemplifies the vibrant literary community that has emerged on Substack. Her writing charts the terrain between casual reader and devoted bibliophile, offering essays on her favourite reads, interviews chronicling the reading lives of fellow book-lovers, and frameworks for cultivating a more sustained reading practice.

She views reading as an antidote to scrolling, and — as her thousands of subscribers can attest — it’s a perspective that continues to resonate with all those who encounter her work each week. Our wideranging conversation explores how she developed her approach and why it matters now.

Jana M. Perkins, PhD

Founder, Women of Letters

Petya K. Grady is a writer and UX strategist. Now entering its sixth year, her popular literary newsletter, A Reading Life, has been named a Substack Featured Publication. Originally from Bulgaria, she lives in Memphis with her family.

How did your childhood shape your ideas about what work looked like and what was possible for you?

Petya K. Grady: I grew up in Bulgaria in the eighties and nineties, and both sets of grandparents lived in villages. They had very working class lives: they had jobs, but also they raised animals, worked farms, and they’re just generally very kind of people of the soil — just very humble, and just really focused on, probably, surviving for most of their lives, based on their age and historically what was going on in that part of the world throughout most of their life.

Both my parents became engineers. During communism, there was a big push for STEM education in our part of the world. I think that Bulgaria still has the largest per capita number of female engineers and computer scientists, as well. So, my mom was a chemical engineer, my dad was an electrical engineer, and they were very kind of proud of having a city life, working prestigious jobs, and also being kind of like serious people.

Everything changed in ’89 with the fall of communism for us. That had just a profound impact on my family, but, I mean, everybody in our country. Things that had always been taken for granted — like employment opportunity for all, social services for all — all of that just kind of disappeared overnight. As a young child— I was born in ’81, so I was eight at the time. I was still very little, but I was not stupid. Our parents did everything they could to just protect us from the chaos of all of that, and were very kind of focused on helping us feel like everything is going to be okay. But, of course, when you’re growing up in such a tumultuous time, you pick up on it even if your parents are trying to tell you that everything’s going to be okay.

So, what that meant was that there was just massive unemployment. A lot of state-run businesses and enterprise was privatized, so people lost their jobs, lost their savings. And my parents kind of dealt with all of that in very different ways. My mom had a really hard time with the transition. She had a very high-level job, in like a microchip production facility. That business shut down and she was unemployed, chronically, for several years during those transition years out of communism. And that took a huge toll on her psyche, because she had previously been very well paid: she ran a team, it was a very prestigious type of industry. And she just could not get over the fact that not only had she lost her job, but she couldn’t find anything— not anything comparable, just anything, period.

As someone who had been so career-focused up until that point, that was very traumatic for her. And then my dad, on the other hand, I don’t know; maybe dissociated better than she did, but he in turn was able to just embrace an entrepreneurial life and started a series of ridiculous businesses. But eventually one of them stuck, and he was able to grow a commercial HVAC business that carried him through most of the remainder of his career. And he had a very fulfilling entrepreneurial life. He’s retired now.

That was my childhood. That was just sort of the background of it, and as I think about how that informed my ideas of work and life— I mean, where to begin?

I feel like I have this really strong idea that work and your job is the most important thing in your life, because it’s the thing that carries you forward. It’s the thing that gets you stuck. It’s the thing that we can get really depressed about. And it just became such a— I don’t know. Just this thing that I assumed my life will be oriented around. Growing up under communism and in our educational system, so much of how we are taught and what the school environment looked like was organized around achievement, academic success, other people knowing how well you were doing in school. Now, at 44, I feel, like, oh my gosh— how toxic and traumatic. You know? This is just too much. It’s a lot.

So, that was my childhood, and I ended up coming to the States in ’99 as an international student to go to college here. I wanted to study political science and become a diplomat and learn about democracy and go home and fix everything. But it felt, at the time, like it was just a path into a big career. That’s what I was thinking about at the time.

Jana M. Perkins: Moving through such a massively destabilizing moment like that — when you saw people in your community, in your own family, even, having done everything right but still being out of work — what kind of impact did that have on you? Did you then feel a sense of responsibility, as you were planning out your own career, to kind of go above and beyond to insulate yourself from something similar happening? Were you always on the lookout for, like, okay, where are the exits? How can I avoid any kind of similar turbulence?

Petya K. Grady: I do think that my whole generation— like, many of us went to school abroad. A lot of Bulgarian kids came to school in the States, a lot ended up in Germany or other places in Western Europe, and I think the biggest driving factor of those choices was to seek professional and economic stability. I’m just gonna go somewhere where I am not gonna have the rug pulled under me unexpectedly. So the stability factor was, I’d say, the biggest motivator.

For me, personally, that did not make me want to go and make more money. I feel like, somehow, what stayed with me was that it can come and then it can go. And the way that that worked itself out in my brain is, like, just do what you need to do: be focused, work hard, end up somewhere that is meaningful and stable. More than, like, “Go start a business! Be entrepreneurial! Take risks!” Because that part of the transition felt really scary to me.

It’s been so many years since I experienced that, and it’s only now in my mid-forties that I’m realizing how much fear that left in me about the world of work and money. It’s just like a year ago that my therapist was, like, “That’s called money trauma.” And it just never occurred to me to think of it that way, simply because it was not something that I individually experienced, but because it was everybody. You know? It was not just my family, and in fact my family probably made its way through that transition less scathed than other families. So I just never really thought to identify that as a source of something to work through. We are just— Eastern Europeans are just so, like, stoic, and no-nonsense, and you just move on, that I’m just finally, like, “No, guys— we need to talk. That was hard.”

Jana M. Perkins: I relate so much to that. As a fellow Balkan girlie— I was born in Croatia.

Petya K. Grady: Oh, okay!

Jana M. Perkins: My family’s from former Yugoslavia. I have such a connection to that part of my identity still. I’m moving back to Croatia pretty soon. I identify so much with a lot of what you shared, and you’re spot on— there is a lot of this internalized trauma that just kind of like, culturally, remains unaddressed. It’s very, like, keep calm and carry on, to the point where people can’t even say, like, “Oh, yeah, that was a trauma. Like, P.S. — that was a trauma.”

Petya K. Grady: Yeah. Yeah, it’s crazy. It’s crazy, and just— I don’t know. For example, waiting in line for bread. And you know that, in our culture, you eat bread with every single meal. This is more a staple [than] like salt and pepper at the table, right?

Having to wait in line for bread, in slushy, dirty, cold, snow, ice in January, and being in this long line— I’m like eight at the time, and I’m standing in line at that store because my parents are either at different stores around the city, because you don’t know— because we may run outta bread, right? So we need to spread and, like, divide and conquer. Or we wait in line for bread, and my dad is further down the line, and then I join a little bit later and we pretend not to know each other so that we can get two pieces of bread, two loaves of bread.

That is a lot for, like, an 8-year-old. And nobody’s— because we’re Eastern European, and because, I think, culturally, everywhere in the world, we’ve changed the way we talk to children. But no one’s like trying to explain this to you, or like contextualize it. So, I’m just— I feel like, every day, I’m discovering something that I’m, like, “I wonder if that’s connected, too.”

Jana M. Perkins: Oh my god, when I tell you that is my life— that is literally my life right now. I’m so connected right now to the diaspora life, the diaspora literature. I didn’t even know— the first time I learned the term ‘diaspora’ was five or six years ago, when I realized that, oh, this is even a phenomenon that people experience. There’s a name for this; there are so many tied experiences. Now that I know that, I’m connecting all of the dots, and just, like, “Oh, okay. Now so much of my identity makes sense.”

Petya K. Grady: So you feel drawn to being part of that community?

Jana M. Perkins: Very much so. I’ve been a lifelong member of the diaspora. We moved to Canada when I was two, so I grew up in Canada. But I had never been able to put words to the fact, or had the thought occur to me, that there was anything about my experience that others had also done. I was always just, like, the outsider trying to live in this new community. But, similar to what you’re saying about only now identifying things from the past and being able to label them— that’s my every day. Some tiny, insignificant thing, I’m like, “Oh, that’s tied to the fact that…” We can talk more off-air about this, maybe, but all of which is to say that I very much identify with that experience.

Petya K. Grady: Yeah. Yeah. It’s so interesting for me— so, I came to the States in ’99, and I was 18 at the time. And at this point I’m 44, so I’ve been here for 26 years now. And it’s been interesting for me to kind of reflect back on just various seasons of my life here, and how at times I felt like… When I was in college, for example, I felt just so embarrassed that I was Bulgarian. Mostly because I felt poor and I felt really embarrassed by my accent. And then I went to grad school, where I was studying political science, and I felt, “Oh, I can have an insider view into a world that I can bring into my work that gives me an edge.”

When I left academia and just got a little bit established in my work — in my professional life, I’ve worked in tech basically more or less since I finished grad school — I always had writing projects going on the side, reading projects going on the side. And I went through this extended period where I was just reading immigrant literature and was writing about it on the internet and was just super involved in understanding my experience as an immigrant. And then at some point that got to feel so exhausting, because I felt like I was trying to maintain in my brain, like, two tracks of life — like, Bulgarian side of existence — that it was just… It’s very difficult to follow two news cycles. And I just got to a point where I was, like, “I just can’t do this. It’s just too much. I feel like when I’m here, I’m always thinking about there. And when I’m there, I’m always thinking about here.”

I was just feeling insane. I just really felt almost… I don’t know. I can’t point out to a specific moment, but, in my mind, a switch flipped at some point and was like, “No, we are here now.” That was maybe 10 years ago, where I was just like, “Okay, so: good, bad, or indifferent, we made a choice. This is where we live, and this is where we’re going to stay planted.” And that made life more peaceful for me. I didn’t like cut ties with my family or anything like that, but I just kind of removed myself— I let myself off the hook for, like, you don’t need to follow what’s going on there politically, detailed, like, you don’t need to follow what books are being published, what people… I couldn’t do that anymore.

Currently, I am in a period where I am starting to feel a lot of nostalgia— I’m gonna cry— just for my parents and my grandparents. Because I think that, now, as a parent myself, I can just see how difficult it was for them. I don’t know. I’m thinking about Bulgaria more than I have in a long time. And also I have an 8-year-old who is really dedicated to being half-Bulgarian. It’s really sweet. So now I’m, like, “Oh, my gosh— here we go again.” So, it’s hard. And I think that being an immigrant is just such an enriching experience: you see so much, you learn so much about yourself. But it’s also very hard.

Jana M. Perkins: Yeah. Especially these days.

Petya K. Grady: Yeah. I know. It feels so cruel to me. And I’ve just had all of the possible paths to immigration. I feel like I’ve had the most seamless, easy way through, because I came on a student visa and I met my now-husband when we were in grad school. So I got a green card through our marriage. And still it has been so difficult. So I just don’t understand the cruelty that we’re witnessing right now for people who have had horrendous, horrific experiences that pushed them out of their homes. And then everything that they’re going through here— it just feels awful right now.

Fast-forward to today. How did the path to what you’re doing now unfold?

Petya K. Grady: So, I feel like… You met me through my Substack, and the way that I was brought up I always assumed that I would have a job that would be, like, working for a company, working for someone, and get paid to do that.

I always was interested in writing, even as a little girl, and I was on a newspaper when I was in high school. I feel like, if you’re a writer, you’re just always looking at the world and telling stories about what you see without even meaning to. It’s just what your brain does. I never seriously considered that as a career path for myself, like, ever.

When I was in college and grad school — so, 2003 through 2006 — that’s when blogs were getting really big. I learned to make websites, and then I always had, like— I had a personal blog, and then I had a literary blog. I just always had this kind of side project going on. And, at some point, I decided to just stop doing that, because I thought, “Just be serious. Do your job. Just do your job, make more money.” That sort of thing.

About two years ago, I had this realization that even though I had a good corporate career, I always had this sense of, “This is not good enough.” Or, “This is fine, but it’s not exactly like what I want,” or, “I got the promotion, and I thought that would feel better.” And then I realized, “Oh, you feel that way because you’re not doing the thing that you really want to be doing, which is reading and writing.” So I went back to what I’d always been passionate about, and I started writing a newsletter on Substack. Mostly for myself, as a form of creative expression, and realized that, like, the moment I started doing that I just felt happier.

So all of that to say is that now I have this side project that is a big part of my life, even though it’s not a job, and even though I don’t know if it will ever be a job or anything that could sustain me monetarily. But I don’t care, because it’s the work that really makes me feel fulfilled. So that has been a journey.

It’s been a journey to get to a point where that feels okay, because the Eastern European in me is like, “But are you getting recognized for it? Are you making a lot of money out of it? Do people know?” And all of these kind of external things that obviously I still pay attention to, but at this point the thing that I’m most proud of in relation to that body of work is that…